A few weeks ago we were asking the question ‘why are two artists from London tramping around in fields 14 miles south of Brussels’.

At 5pm on 18th of June we jumped on Eurostar heading to Brussels, at 10.30 the next morning we were on a train to Braine-l’Alleud to join the crowds walking the two miles to the site of the Battle of Waterloo (1815), and for the following two days we were to wander, cameras in hand exploring the sights and sounds of Waterloo 2015.

The answer to ‘why were we there?’ First of all we were there to enjoy the event, but also to collect photos & video for a future piece of work – but over the two days we roamed the site we realised that it defined many of the interests that drive our art. After three weeks what remain in the memory are the scale and above all the curious mixture of fact and fiction posed by the event (both of which are major ingredients of our work).

We are all now living in the ‘computer age’ – even if we don’t possess a pc or smartphone the world around us is run by computer and the individual is monitored and recorded from afar. As computer literate artists we spend a lot of time researching and surfing the ‘net’ for ideas, exploring and matching various fragments of information – some proven facts and some more imaginative – which we splice together to create surreal metaphors that question the true nature of our ‘virtual/real existence. Like many internet researchers our overriding conclusion is that the integrity of web facts is often highly questionable, but instead of seeing that as a negative in society we embrace it as the dominant metaphor of contemporary life and the main subject of our work.

In our work history often provides a stable structure within which we weave an alternative narrative of fiction through the fragments of static fact. The re-enactment of Waterloo perfectly illustrates our interest in the subject, mixing fact and fiction, reality and the virtual.

A common perception of overweight middle-aged men dressed in ill-fitted ‘costumes’ playing soldiers with the plastic reality of a computer game was far from the truth, this was no village fete. The encampments, arena and various assorted museums/shops/cafes were scattered over the original battlefield covering approximately four square miles.

Throughout the two days there were moments that created a curious sense of time freezing (often they were mundane experiences away from the main events), such as seeing a group of French gunners struggling at the side of the main Brussels road to hitch their 6lb cannon onto their horse drawn lumber, or the 300 plus French infantry marching up and down an isolated field practising their drill while their officers shouted at them. But some of the more memorable were found walking around the encampments listening to the multitude of foreign languages bursting into song or joking over their hot meals prepared in a massive pot suspended over an open fire.

Walking back along the road from the French encampment with thousands of other spectators, tired and eager to find our places in the arena for the first evening battle we were stopped by police who’d blocked the road creating a partition stretching from one side to the other – leading into the arena. The crowd tired and agitated, started shouting.

Looking over the head of the guy in front I realised where we were – at the gate of the farmhouse ‘La Haye Sainte’ (a building at the centre of the battle). a group of Prussian gunners appeared dragging a massive cannon through the farmhouse gates across the road, past the now inquisitive crowd and into the arena entrance, this was followed by a company of infantry.

I managed to peer past the heads to the interior of the farm – there were hundreds of soldiers with 20 or more cannons, groups of infantry and assorted civilians all were waiting to cross into the arena. Even though we were tired and wanted to move on I was struck by the spectacle – the thought that 200 years before a similar scene would have been played out, watching the sheer physical effort to move some of those heavy cannon created a lot of respect for those taking part – providing a truly human experience that links to the truth laying at the foundation of our history.

Walking around the camps, spending time watching them complete their daily chores, cook their food, practice their drills and clean equipment we noticed the camaraderie developing between them (produced by their shared experience and resembling the cadence of true combatants) encouraged and emphasized in the variety of languages present had produced an undeniable, substantial and effective ‘reality’ to the occasion.

The Battle of Waterloo fought in this space on the 18th of June 1815 stands as a defining moment in European history, ending twenty years of possibly the first truly global war and laying the ground for one hundred years of peace.

With approximately 72,000 French, 68,000 British & Allied & 50,000 Prussian soldiers competing for four square miles of land 20 mins train ride from Brussels this was to be the bloodiest battle to date – only to be surpassed by the slaughter of WW1 one hundred years later. Over the 9 hours of fighting 50,000 would be killed & wounded, and as evening came Napoleon’s future for France would come to an end.

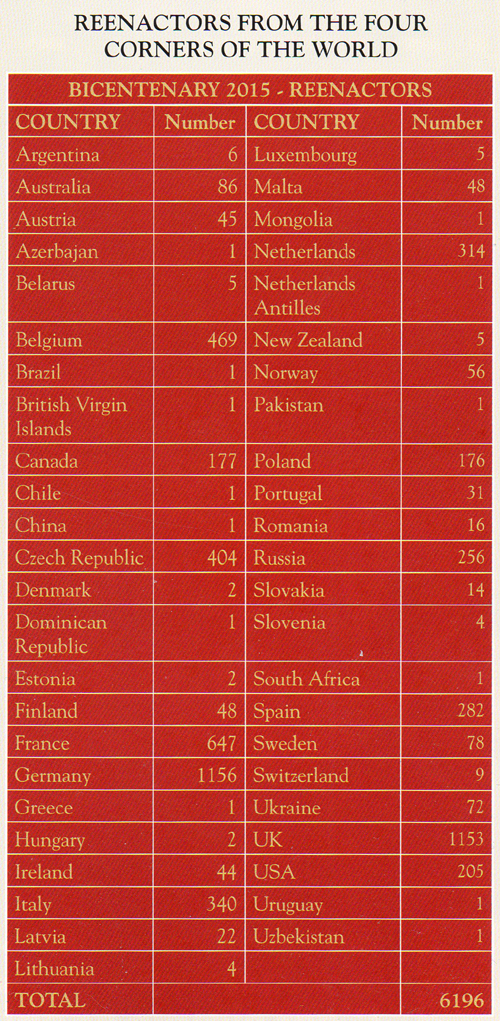

There is a mere fraction of reenactors (approx 6,000) compared to the original participants, but when you add the thousands of spectators (approx 200,000 over the weekend) it comes close to the original footfall. Both armies in 1815 were comprised of many nationalities – the fact that this event (the biggest of its type) managed to assemble so many nationalities just added to the layers of reality & depth of experience.

It appears that whether you immerse yourself in computer games, social media, TV or take part in events like this there is a growing reliance on a virtual form of life that adds to and enhances our reality. The need to create alternate versions of ourselves, to lift us from the mundane is adjusting our experience of reality – if you spend half of your life ‘online’ or living as an alternate version of yourself then that will partly define your reality.

As we left the battle late on Saturday evening it was as if a fog had descended over the area, the smoke from the guns that had blurred the battlefield for the past half hour (eloquently rendering the confusion of Napoleonic warfare) had spread for miles – we could still see the flames from the cannons lighting the mist as we joined the thousands heading back to their own versions of reality.

The sheer physical number of participants, their dedication and mixture of nationalities raised the event far beyond the common garden variety of home grown historical re-interpretation, creating a truly epic scale and produced a cinematic effect blurring the lines between fiction and reality.

On a personal note I really enjoyed the WaterlooTrois beer – I thoroughly recommend!

Here’s a collection of some of our images.